In JC’s Newsletter, I share the articles, documentaries, and books I enjoyed the most in the last week, with some comments on how we relate to them at Alan. I do not endorse all the articles I share, they are up for debate.

I’m doing it because a) I love reading, it is the way that I get most of my ideas, b) I’m already sharing those ideas with my team, and c) I would love to get your perspective on those.

If you are not subscribed yet, it's right here!

If you like it, please share it on social networks!

🔎 Some topics we will cover this week

Finding product-market-fit with intuition and customer interaction

Planning and decision making in uncertain times

Software engineering and its best practices

Identifying and solving problems

👉 Operators Optimizing for Optics, Thread by Shreyas Doshi (Threadreader)

❓Why am I sharing this article?

Excellent thread about what kind of leadership is needed for early stage projects (like Mind)

How to not work for optics, to don’t over-abuse of frameworks, OKRs,... to be focused on finding product-market-fit with craft, intuitions, and a ton of time spent with customers.

Why do companies with major resources & distribution make products that are mediocre & often fail to reach their potential?

There are a handful of reasons, many of which you already know. But there is one under-discussed reason: Operators Optimizing for Optics

The tendency of ambitious Operators to manage new initiatives for Optics rather than for Impact, and get rewarded for it.

The Operator:

Excellent at: scaling teams, cross-org alignment, unblocking execution

Superpower: communication

Not excellent at: original product insight

Loves spending time with: peers & company execs

Early on: gets promoted on potential

Is often a PM talent magnet

Operators are great for scaling, at the right time, but they can bring premature optimization to projects, and that can kill its prospects very early on (even if most folks can’t see that readily, it is already dead). He could have hired great Craftspeople like Jessie on his team, and then listened to those Craftspeople to translate founder’s vision to a winning product.

The Craftperson

Excellent at: defining products & strategy, mentoring PMs

Superpower: product insight

Not excellent at: dealing with large orgs & its taxes

Loves spending time with: team, users

Early on: gets promoted on talent

Makes singular product impact

The exec team should have understood that a lot of what seemed like “great operations & management” actually hurts early-stage bold initiatives. Premature operational optimization can be a very bad thing for early-stage projects in startups & large companies.

Founder should have had the leadership maturity to see through (and candidly call out) what Dan was doing: managing for Optics, rather than a) actually understanding users, b) instilling creativity & humility, and c) optimizing for major impact.

Operators are everywhere in tech companies. They are extremely valuable. But, assigning an Operator who is not self-aware to the wrong project can be fatal for the project & the team. You see, many Operators, even if they have good intentions, do not understand the role of a leader of an early stage initiative.

Operators think that their job is to understand what the CEO wants, orchestrate actions across the org based on that, and set up processes, structures, and accountability checks to ensure that those actions are performed efficiently.

For any early stage product initiative, its leader ought to deeply understand the user & business problems to be solved, build a small, energetic team that is inspired to solve them, build product to test informed hypotheses, with the most basic process to support these actions.

Yes, it does matter what the Founder/CEO thinks. Yes, the Founder’s vision is to be understood & taken seriously. But every Founder worth their salt knows that real product work isn’t just about transcribing his/her vision. New product work is messy, requires enormous creativity. What should Operators who want to get better at leading early stage products do?

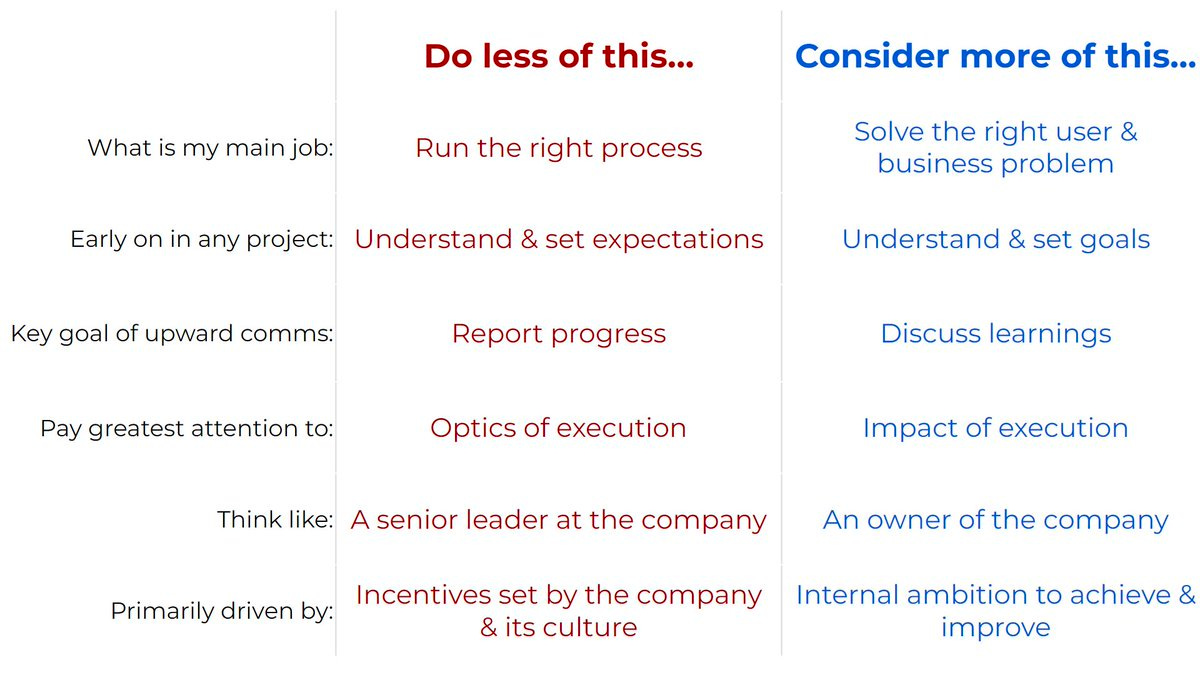

So let me conclude this thread with my prescription of what such Operators should do less of, and start doing more of [see image]:

A few concrete signs that “optimizing for optics” *might be* happening for early-stage products in your org:

1) Rush to create (and show) certainty for inherently ambiguous problems & ideas

2) Team makes decisions & writes proposals based on what they think the “Founder/CEO wants to hear”

3) Impatience (and push from the leader) to start writing code

4) Related, a lot of emphasis on “showing visible progress” early on

5) Citing process, rules, OKRs, org structure as a definitive reason not to do something that is otherwise right

6) Prematurely polished metrics dashboards

7) Using small absolute improvements but large relative improvements as validation, communicating these widely (“signups grew 60% last week”. narrator: “they went from 50/week to 80/week. they had also dropped from 60 to 50 the week before. smaller competitor is doing 2000/week”)

8) Citing any confirming feedback/data loudly, explaining away disconfirming stuff as not relevant

9) Leader asks people “to believe in the mission / vision” when tough questions get asked

10) Pressure to under-promise & over-deliver

11) Unusual degree of celebration when Founder/CEO appreciates “input artifacts” (e.g. “Bob said that was a great product review & doc - well done team - congrats to us - just another validation of the great work you are all doing - we're going to crush it - small party at 5 pm”).

👉 Annual Planning in Uncertain Times: 6 Tactics for Rethinking Your Company’s End-of-Year Exercise (First Round Review)

❓Why am I sharing this article?

Should we budget in Q2 instead of Q4 given our seasonality?

I found BPM very interesting. It is also why I prefer NCTs (narrative, commitments, tasks) to OKRs.

“The W Framework”

Context: Leadership shares a high-level strategy with teams

Plans: Teams respond with a proposed plan

Integration: Leadership integrates into a single plan and shares it with teams

Buy-In: Teams make final tweaks, confirm buy-in and get rolling

The thing that I've noticed about OKRs is that the objectives aren't prioritized in most companies,” says Jeff Lawson, CEO and co-founder of Twilio.

“At most companies, the energy of OKRs is really around the key results. Everybody gets very focused on the metrics. But metrics are, in my opinion, the least important part of an annual plan because they’re not very strategic.”

The metrics tell us if we're on the right path. But charting the right path is actually the hard work.

Instead, Twilio uses a system called BPMs — big picture, priorities and measures.

Big picture: 2-3 sentences about what the team wants to accomplish in the next 5-7 years, based on what leadership has outlined in their long-range plan.

Priorities: 5-10 efforts to prioritize over the next 12-18 months. Think of this as what needs to be done to get to the big picture.

Measures: Markers that tell you if you’re making the progress you want toward the priorities.

👉 What Distinguishes Great Software Engineers? (Abi Noda)

❓Why am I sharing this article?

I found this description very accurate and interesting.

Effective decision-making may be an overlooked skill for developers.

The analysis yielded the top five attributes that distinguish great engineers: “writing good code, adjusting behaviors to account for future value and costs, practicing informed decision-making, avoiding making others’ jobs harder, and learning continuously.”

Being a competent coder: Paying attention to details, mentally capable of handling complexity

Maximizing current value of their work: Anticipating future needs, avoids analysis paralysis, intentional about trade-offs. Great engineers distinguish themselves from others by considering the context of their software product, maximizing the value of their current actions; adjusted for probable future value and costs.

Practicing informed decision-making: Gathering information to make informed decisions, data-driven, open-minded

Enabling others to make decisions efficiently: Creates shared understanding with others, creates shared success. Great engineers distinguished themselves by making others’ jobs easier, helping them to make their decisions more efficiently (or, at minimum, they did not make them worse).

Continuous learning: Desire, ability, and capacity to learn or figure out how something works

👉 Amazon CEO Andy Jassy is trying to fix a crumbling engineering culture with a new unit that tackles ‘foundational pain points’ raised by the company’s frustrated developers (Business Insider)

❓Why am I sharing this article?

What they did might be interesting for Foundation and how we want to improve our developer experience.

I liked their tenets

Earlier this year, Amazon formed the "Amazon Software Builder Experience" group with the ambitious goal of turning the internet giant into "Earth's best employer for software builders". Since launching, the ASBX team has grown to more than 400 employees, working on code automation, improved developer tools, and enhanced tutorials and safety infrastructure.

"We also want developers to feel like they can spend most of their time building as opposed to reinventing manual tools that are being repeated. And we intend to fix that."

And here are the six tenets, or guiding principles, the ASBX team is using, according to one of the documents:

1. Software builders across Amazon require consistent, interoperable, and extensible tools to construct and operate applications at our peculiar scale; organizations will extend on our solutions for their specialized business needs.

2. Amazon's customers benefit when software builders spend time on novel innovation. Undifferentiated work elimination, automation, and integrated opinionated tooling reserve human interaction for high judgment situations.

3. Our tools must be available for use even in the worst of times, which happens to be when software builders may most need to use them: we must be available even when others are not.

4. Software builder experience is the summation of tools, processes, and technology owned throughout the company, relentlessly improved through the use of well-understood metrics, actionable insights, and knowledge sharing.

5. Amazon's industry-leading technology and access to top experts in many fields provides opportunities for builders to learn and grow at a rate unparalleled in the industry.

6. As builders we are in a unique position to codify Amazon's values into the technical foundations; we foster a culture of belonging by ensuring our tools, training, and events are inclusive and accessible by design.

👉 OPP (Other People’s Problems) (Medium)

❓Why am I sharing this article?

I’m not sure I’m aligned with all parts of the advice here, but overall knowing where to spend time and what problems to solve is a key strength to develop.

Figuring out how to pick my battles

There isn’t a job where you can fix all the things. There’s always going to be something you can’t fix.

Step one: Figure out who owns this problem

If it’s your job (or the job of someone who reports to you), great. Go to it! Make systems that are as robust as you believe systems should be. Follow processes that you believe are effective and efficient

If there’s no clear owner, do you know why? Is it just because no one has gotten around to doing it, or has the organization specifically decided not to do it? If no one’s gotten around to doing it, can you do it yourself? Can your org do it, just within your org?

If it’s someone else’s job, how much does it affect your day to day life? Does it bother you because they’re doing it wrong, or does it actually, really, significantly make it harder for you to do your job? Really? That significantly? There’s no work around at all? If it is not directly affecting your job, drop it!

Step two: Talk to all the people

If you don’t clearly own the problem, you need to talk to people. If you feel tired by the idea of talking to all people, stop! This is a sign that you should not pick this battle!

If you’re ok with talking to all the people, then get out there and get a sense of the problem beyond you and your team. You can do this formally, with a document that you prepare addressing the problem as you see it, or informally, as a series of user interviews.

If you know who should own this, you need to give them a chance to fix it. Which means you need to come with examples of how the problem is impacting you or your team.

Step three: Plan the fix

Make a concrete plan for how you will fix it, and share that plan with the people who need to know about it.

You should expect that you will need to get feedback and revise your plan, and the amount of feedback and revision required will be directly related to how big the problem is, how many people it impacts, and how controversial the fix you’re proposing is.

Expect this feedback, buy-in, and revision process to take a while. Be sure to include your skeptics too.

👉 Fatal flows (Warren Craddock, Twitter thread)

❓Why am I sharing this article?

It’s hard to understand why a team/company continues to work on a product with an obvious fatal flaw

It’s a good conversation starter for “should we really focus our energy on this?”

From an engineer who worked on Lytro, Google Glass and Google Clips extracts:

The cultures often grow to silence or downplay fatal flaws in the product, perhaps because it must be done to keep people marching along together.

If you notice such a fatal flaw in your own project, you’re probably not alone.

Your colleagues probably notice it, too.

Build culture where people can say, “this is an unsolved problem, and we may not have a viable product if it is not solved.”

👉 11 Laws of Software Estimation for Complex Work - Maarten Dalmijn

❓Why am I sharing this article?

It puts great words on hunches we have about estimations and their (un)usefulness

Law 8, Keeping things simple is the best way to increase the accuracy of estimates, is I think the most interesting one.

The work still takes the same amount of time regardless of the accuracy of your estimate.

No matter what you do, estimates can never be fully trusted.

Imposing estimates on others is a recipe for disaster.

Estimates become more reliable closer to the completion of the project. This is also when they are the least useful.

The more you worry about your estimates, the more certain you can be that you have bigger things you should be worrying about instead.

When you suck at building software, your estimates will suck. When you’re great at building software, your estimates will be mediocre.

The biggest value in estimating isn’t the estimate but checking if there is a common understanding.

Keeping things simple is the best way to increase the accuracy of estimates.

Building something increases the accuracy of estimates more than talking about building it.

Breaking all the work down to the smallest details to arrive at a better estimate means you will deliver the project later than if you hadn’t done that.

Punishing wrong estimates is often like punishing a kid for something they don’t and can’t know yet.

It’s already over! Please share JC’s Newsletter with your friends, and subscribe 👇

Let’s talk about this together on LinkedIn or on Twitter. Have a good week!