Dear friends,

In JC’s Newsletter, I share the articles, documentaries, and books I enjoyed the most in the last week, with some comments on how we relate to them at Alan. I do not endorse all the articles I share, they are up for debate.

I’m doing it because a) I love reading, it is the way that I get most of my ideas, b) I’m already sharing those ideas with my team, and c) I would love to get your perspective on those.

If you are not subscribed yet, it's right here!

If you like it, please share it on social networks!

🔎 Some topics we will cover this week

Key metrics to evaluate SaaS companies

Understanding the “rule of 200” and the importance of “owning your balance sheet”

Understanding the different financial markets and how to adapt to future ones

👉 The SaaS Metrics That Matter (Bottom Up by David Sacks)

❓ Why am I sharing this article?

I found the depth of the analysis and tables very helpful to know what to look at.

We’re also releasing our internal tool, SaaSGrid, which we’ve used to analyze KPIs for hundreds of SaaS companies, as a free publicly-available tool to help founders calculate metrics (anonymously if they wish) for their own startups.

CMGR:

What’s the best way to measure growth in MRR?

Use a CAGR calculator but on a monthly basis

This is called Compound Monthly Growth Rate (CMGR).

A CMGR of 10% is about 3x year-over-year growth.

MRR Components: Breaking down MRR into its key components helps to understand changes in MRR over time.

Retained – MRR retained from existing customers;

Expansion – MRR added from existing customers;

New Sales – MRR added from new customers;

Resurrected – MRR added from former customers;

Contraction – MRR lost from customer downgrades; and

Churned – MRR lost from churned customers.

Retention is analyzed by grouping customers into “cohorts” according to their sign-up period (month, quarter or year), then tracking what percentage of the original cohort remains over time. Understanding retention rates of monthly cohorts, typically at months 12 and 24, is vital to the health of the business, as a fast growth rate in new signups can mask high churn rates in older, smaller cohorts.

Dollar Retention: Also known as Net Revenue Retention (NRR), Dollar Retention measures how much revenue a cohort is generating in each period relative to its original size.

Dollar Retention takes expansion revenue into account, and can be greater than 100% if expansion exceeds churned and contracted revenue.

The best SaaS companies have 120%+ Dollar Retention each year. Dollar Retention of less than 100% per year is evidence of a Leaky Bucket and is problematic.

Logo Retention:

Logo Retention measures the percent of customers that stay active (non-churned).

Logo Retention can never be higher than 100% since the number of logos can’t expand.

As a result, Logo Retention is usually much lower than Dollar Retention.

Logo Retention is typically a function of customer size: 90-95% is common for enterprises, 85% for mid-market, and 70-80% for small businesses.

Dollar Retention is much more important than Logo Retention.

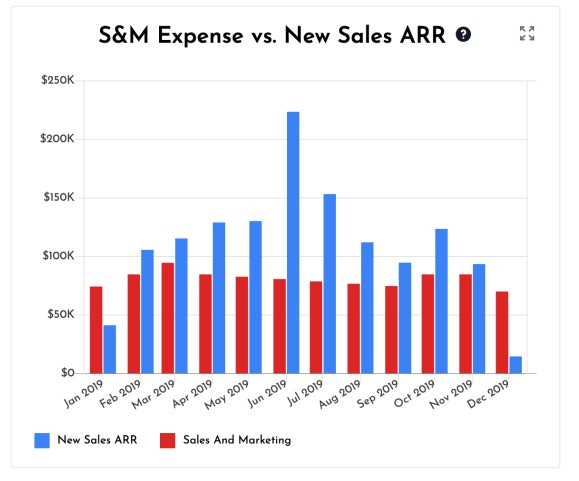

New Sales ARR vs S&M Expense: How much did the Sales & Marketing (S&M) departments (inclusive of all programs and personnel) spend compared to how much New Sales ARR (ARR from new customers only) was added in the same period? Ideally, New Sales ARR is equal to or greater than S&M spending.

LTV: Lifetime Value (LTV) is the cumulative gross profit contribution, net of CAC, of the average customer in a cohort.

Healthy cohorts cross the $0 LTV line before month 12, and LTV grows to at least 3x original CAC over time.

Burn Multiple:

The Burn Multiple is a company’s Net Burn divided by its Net New ARR in a given period (typically annually or quarterly).

The lower the Burn Multiple, the more efficient the growth is. For fast-growing SaaS companies, a Burn Multiple of less than one is amazing, but anything less than two is still quite good.

👉 Fintech and the Pursuit of the Prize - Who Stands to Win Over the Next Decade? (Coatue)

❓ Why am I sharing this article?

Healthcare is one of the biggest opportunities in the world

Alan's rule of 200 is good :)

The importance of owning your balance sheet to control your destiny (which has always been our strategy)

“Maniacal bundling is critical for Fintechs survival”

Market opportunities:

Key metrics:

Month 12 $ Retention %

(+) YoY Revenue Growth %

(+) Gross Margin %

(+) Operating Margin %

= “Rule of 200”If we had to pick a single metric to make an investment decision it is month 12 retention

Bundling:

FinTechs should not be afraid to own balance sheets in order to control their destiny

B2B vs. B2C:

B2B is fundamentally “easier” than B2C

Maniacal bundling is critical for Fintechs survival

B2C Avg. Retention 94%

B2B Avg. Retention 125%

👉 Howard Marks: Sea Change (Oak Tree)

❓ Why am I sharing this article?

Understanding the different financial markets and how to adapt to future ones

How wage increases in context of inflation leads to more price increases which leads to a spiral

It is only an analysis among others, but confirms that being long-term and not needing capital is an extremely good situation to be in.

In my 53 years in the investment world, I’ve seen a number of economic cycles, pendulum swings, manias and panics, bubbles and crashes, but I remember only two real sea changes. I think we may be in the midst of a third one today.

The previous sea changes:

Because the U.S. private sector in the 1970s was much more unionized than it is now and many collective bargaining agreements contained automatic cost-of-living adjustments, rising inflation triggered wage increases, which exacerbated inflation and led to yet more wage increases. This seemingly unstoppable upward spiral kindled strong inflationary expectations, which in many cases became self-fulfilling, as is their nature.

Volcker’s actions ushered in a declining-interest-rate environment that prevailed for four decades (much more on this in the section that follows). I consider this the second sea change I’ve seen in my career.

The long-term decline in interest rates began just a few years after the advent of risk/return thinking, and I view the combination of the two as having given rise to (a) the rebirth of optimism among investors, (b) the pursuit of profit through aggressive investment vehicles, and (c) an incredible four decades for the stock market. A compound annual return of 10.3% per year. What a period!

There can be no greater financial and investment career luck than to have participated in it.

What are the effects of declining interest rates?

They accelerate the growth of the economy by making it cheaper for consumers to buy on credit and for companies to invest in facilities, equipment, and inventory.

They provide a subsidy to borrowers (at the expense of lenders and savers).

They increase the fair value of assets. (The theoretical value of an asset is defined as the discounted present value of its future cash flows. The lower the discount rate, the higher the present value.) Thus, as interest rates fall, valuation parameters such as p/e ratios and enterprise values rise, and cap rates on real estate decline.

They reduce the prospective returns investors demand from investments they’re considering, thereby increasing the prices they’ll pay. This can be seen most directly in the bond market – everyone knows it’s “rates down; prices up” – but it works throughout the investment world.

By lifting asset prices, they create a “wealth effect” that makes people feel richer and thus more willing to spend.

The overall period from 2009 through 2021 (with the exception of a few months in 2020) was one in which optimism prevailed among investors and worry was minimal.

The current context:

All of the above flipped in the last year or so.

Higher interest rates led to higher demanded returns. Thus, stocks that had seemed fairly valued when interest rates were minimal fell to lower p/e ratios that were commensurate with higher rates.

Falling stock and bond prices caused FOMO to dry up and fear of loss to replace it.

The markets’ decline gathered steam, and the things that had done best in 2020 and 2021 (tech, software, SPACs, and cryptocurrency) now did the worst, further dampening psychology.

The Ukraine conflict reduced supplies of grain and oil & gas, adding to inflationary pressures.

The expectation of a recession also increased the fear of rising debt defaults.

New security issuance became difficult.

Having committed to fund buyouts in a lower-interest-rate environment, banks found themselves with many billions of dollars of “hung” bridge loans unsaleable at par. These loans have saddled the banks with big losses.

These hung loans forced banks to reduce the amounts they could commit to new deals, making it harder for buyers to finance acquisitions.

Inflation and interest rates are highly likely to remain the dominant considerations influencing the investment environment for the next several years.

People who came into the business world after 2008 – or veteran investors with short memories – might think of today’s interest rates as elevated. But they’re not in the longer sweep of history, meaning there’s no obvious reason why they should be lower.

It’s already over! Please share JC’s Newsletter with your friends, and subscribe 👇

Let’s talk about this together on LinkedIn or on Twitter. Have a good week!